L'Assiette au Beurre, 28 septembre 1901

By ROBERT JUSTIN GOLDSTEIN Oakland University.

Published in Michigan Academician , volume XXX, March, 1998, pp. 107-122.

In nineteenth-century Europe, large segments of the poor population could not read, but they were

not immune from influence from other forms of mass communication. In this age before television, radio, and cinema, caricatures were especially feared by the ruling orders as potentially critical

and threatening. As a result, in every major European country except for England, caricatures were subject to prior censorship for part or most of the 1815-1914 period, and in some countries such

regulations were maintained well after prior censorship was abolished for the printed word. Thus, in France, the printed word was not subject te, prior censorship after 1822, while caricatures

were almost continuously subject to prior governmental until 1881. (1)

Most studies which have touched on the subject of caricature censorship in nineteenth century Europe have focused on each government's censorship of caricatures produced in its own country and

perceived as posing a threat to its own rule. However, in many cases the feared repercussions of critical political caricatures were so great that nineteenth-century European authorities went

beyond attempting to prevent artistic criticism of themselves in journals published in their own country. Regimes also tried to ban importation from abroad of critical caricature journals or

pressured foreign governments to forbid the publication of drawings which were viewed as subversive, and, for fear of diplomatic complications, sometimes refused to allow the publication in their

own country of caricatures which were viewed as threatening their relations with foreign governments. This article seeks to explore the previously almost entirely neglected international aspects

of nineteenth-century European caricature censorship (casing the historian's definition of "nineteenth century" as covering from 1815 to 1914).

FIGURE 1. In 1843, the British caricature journal Punch published this caricature satirizing French officials for banning the magazine.

"Among the

means employed to shake and destroy the sentiments of reserve and morality which are so essential to conserve in the bosom of a well-ordered society, drawings are one of the most dangerous. This

is because the worst page of a bad book requires some rime to read and a certain degree of intelligence to understand, while the drawing offers a sort of personification of the thought, it puts

it in relief, it communicates with movement and life, so as to thus present spontaneously, in a translation which everyone can understand, this most dangerous of all seductions, that of

example".(3)

Political caricatures were viewed as especially dangerous because their impact was seen as greater and more immediate than that of the

printed word and because, while large segments of the especially feared "dark masses" were illiterate and thus not susceptible to, subversive words, anyone could understand the meaning of a

drawing. For example, in 1823 the Paris Police Prefect urged a crackdown on itinerant sellers of prints, since such traders frequently spread dangerous ideas among the "lower classes of society."

In 1829 the interior minister told his prefects, concerning the circulation of Napoleonic images, "In general, that which can permitted without difficulty when it is a question of expensive

engravings, or lithographs intended only to illustrate an important [i.e., expensive] work, would be dangerous and must be forbidden when these same subjects are reproduced in engravings and

lithographs at a cheap price." He added that drawings were especially dangerous because they "act immediately upon the imagination of the people, like a book which is read with the speed of

light." Referring to the French laws requiring prior censorship of drawings and caricatures, he added, "It is then extremely important to forbid all which breathes a guilty intention in this

regard."(2)

Similar concerns were also clearly expressed when the French police minister instructed his subordinates throughout the country to harshly enforce prior censorship of caricature regulations in a

directive of Match 30, 1852 :

Describing both the enormous popularity and impact of caricatures, a bureaucrat stationed in the French City of Rouen in 1869 informed his superiors in Paris that while the "great Parisian newspapers play a role in the movement of public opinion, that which dominates it especially" was the "illustrated journals of opinion" which "sell many more examples and are read much more than the serious organs of the same opinion" and which each day spread "scorn and calumny on all that concerns the government" and "by ridicule, by perfidious jesting and defamations" were "succeeding among all classes" in a campaign of "war on our institutions and those who personify them." Such concerns were by no means confined to officials in France. For example, in 1843 the Prussian Minister of the Interior successfully urged King Frederick William IV to reimpose the recently-abolished censorship of drawings by arguing that caricatures "prepare for the destructive influence of negative philosophies and democratic spokesmen and authors," especially since the "uneducated classes do not pay much attention to the printed word" but they do "pay attention to caricatures and understand them" and "to refute [a caricature] is impossible, its impression is lasting and sometimes ineradicable." Even in the United States, the notoriously corrupt New York City politician William "Boss" Tweed, who was repeatedly targeted by the brilliant caricaturist Thomas Nast during the post-Civil War period, declared, "Those damned pictures; I don't care so much what the papers write about me - my constituents can't read, but damn it they can see pictures! "(4)

Aside from the fact that the impact of drawings was seen as more immediate than that of the printed

word and more accessible to the illiterate, caricatures were also seen as more threatening than words because they were perceived as more visceral and therefore more powerful. In successfully

urging the French legislature in 1835 to reimpose censorship of drawings, which had been halted in the aftermath of the 1830 July Revolution, French Minister of Commerce Charles Duchatel told the

legislature that "there is nothing more dangerous, gentlemen, than these infamous caricatures, these seditious designs," which "produce the most deadly effect." His argument was supported by

another legislator who proclaimed that the 1830 constitutional charter's apparent ban on all forms of censorship guaranteed only the freedom to express opinions, and he said that it would "force

the meaning of words to consider drawings the same as opinions" or to "establish a parallel between writings which address themselves to the mind and the illustration which speaks to the senses.

The vivacity and popularity of the impressions they leave must create for drawings a special danger which well-intended legislation must prevent at all costs." An especially good summary of the

fears provoked by caricatures was offered by conservative French legislative deputy Emile Villiers to his colleagues in 1880 : “I believe that, if the

liberty of the press, practiced without restraint or regulation, poses problems and dangers, the unlimited freedom of drawings presents many more still. An article in a journal only affects the

reader of the newspaper, he who takes the trouble to read it; a drawing strikes the sight of passersby, addresses itself to all ages and both sexes, startles not only the mind but the eyes. It is

a means of speaking even to the illiterate, of stirring up passions, without reason¬ing, without discourse.” (5)

Given the perceived power of political caricatures, it is not surprising that their usage sometimes had international ramifications

even before they became increasingly widely distributed during the nineteenth century. For example, a French Revolution-era English observer recalled the policy of the Dutch government under

William of Orange in the late eighteenth century of subsidizing the publication of caricatures which attacked King Louis XIV of France for his attempts to subdue the Netherlands : “King

William, whose whole life was spent in raising and keeping alive the Spirit of Nations against France, saw well the Importance of this vehicle [caricatures] as an Engine of State. On the

Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, he spread engravings of the Sufferings of Protestants in France all over the ports of Europe; by which he added the Courage of Reason to that of Passion in

those who saw them; and raised a higher storm against Louis the Fourteenth than ever his own Persecutions had done.” (6)

The use of caricatures for international propaganda purposes reached previously unknown heights during the French Revolution, as English caricaturists such as James Gillray fought France with

brutal pictorial assaults on Napoleon and the excesses of the French Revolution. Such prints were widely distributed and extremely popular. A French émigré living in England described the scene

when a new Gillray print was displayed at a leading English print shop in 1802 : “If men be fighting over there for

their possessions and their bodies against the Corsican robber [Napoleon], they are fighting here to be the first in Ackermann's shops and see Gillray's latest caricatures. The enthusiasm is

indescribable when the next drawing appears; it is a veritable madness. You have to make your way through the crowd with your fists.”

Napoleon responded to the English caricature attacks

by commissioning and subsidizing French artists to respond in kind. Thus on May 3, 1805, he directed his secret police chief, Joseph Fouché, to "Have some caricatures made; an Englishman, purse

in hand, begging different powers to receive his money, etc.... The immense attention which the English direct to gaining time by false news shows the extreme importance of this work." (7)

As a result of the perceived power of caricatures and their well-established use for international propaganda purposes, governments sought to extend their control beyond their own borders and, in

some cases, sought to ban caricatures published within their own countries that criticized foreign regimes if such criticism was seen as threatening diplomatic relations or initiatives. Louis XIV

and subsequent eighteenth-century French governments sought, usually with little success, to ban importation of hostile caricatures published in the Netherlands (often by French political or

religious exiles), while Napoleon was so infuriated by the flood of hostile English caricatures that at one point during diplomatic negotiations he even formally demanded that the British

govern¬ment forbid the publication of caricatures "made in the pay of the emigration." (8)

During the nineteenth century, the effort of European governments to forestall publication or importation of hostile caricatures from abroad and the publication of domestic caricatures which

might contradict their foreign policy goals became increasingly systematic as the development of new printing techniques and better communications and transportation networks greatly facilitated

the distribution of printed materials. During the pre-1848 period, when European politics was generally dominated by the reactionary spirit of Austrian Foreign Minister Clemens von Metternich,

the major countries of Europe generally collaborated with each other to suppress political dissent. All of the major regimes except for Great Britain imposed prior censorship of caricatures and

forbade virtually all political designs. As a result, few caricatures that might cause international repercussions saw the light of day or required any overt or covert protests or action. Thus,

in Restoration France (1815-30), the government prevented the publication of all caricatures that could lead to diplomatic complications. (9)

However, a few examples of published caricatures that led to international complications can be found for the pre-1848 period. For example, after the pro-Napoleonic journal Naun Jaune,

one of the first papers to regularly feature caricatures, was suppressed in France in 1815 and reconstituted itself in exile as the Naun Jaune Refugie, the French government

placed intense and apparently successful diplomatic pressure on the Dutch government to suppress it. On the other hand, England, which had been the source of so many anti-Napoleonic caricatures

between 1800 and 1815, ironically became a major center during the Restoration for the publishing and smuggling into France of pro-Napoleonic prints, as well as other banned drawings, such as

those attacking King Louis XVIII. When English caricaturists continued to attack France even after the restored Bourbon dynasty was overthrown in the 1830 "July Revolution," the new regime of

King Louis Philippe formally banned the leading English caricature journal Punch from France during the 1840s (a period when Punch was also banned from Austria). (10)

Punch responded in 1843 by publishing a cartoon showing its namesake character being turned back by a French customs official at Boulogne (Figure 1), accompanied by a letter from "Punch"

reporting that he had been informed that "it is henceforth not permitted that your blood shall circulate in France." According to "Punch," among the sins the French authorities' correct were

questioning "the born right of every Frenchman to carry fire and bloodshed into every country he can get into" and denouncing "what is as dear to every Frenchman as the recollection of his

mother's milk, an undying hatred, to England and all that's English.” (11)

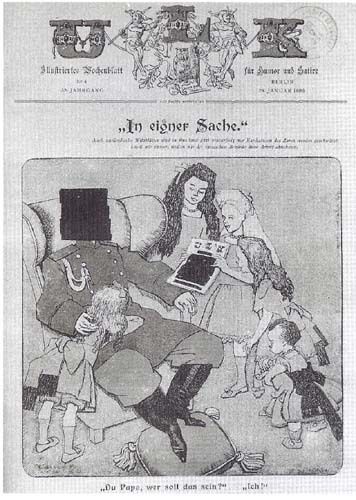

FIGURE 2. In its issue of January 26, 1905, the German caricature Ulk satirized the rigid censorship of caricature in Russia.

The Russian government was especially thin-skinned about any pictorial criticism. In 1830, the Russian ambassador to Germany complained bitterly that caricatures being displayed in Berlin shop windows sympathetic to the Polish revolt of that year were "calculated to arouse hate of the Russian government." In 1848, a year of successful revolution (and the temporary abolition of censorship of caricature) in France but increased repression in Russia, the French caricature journal Le Charivari lampooned the Russian hatred of caricatures by printing a drawing depicting a Russian officer spotting a soldier reading a copy of Le Charivari and declaring, "Let's shoot him!" The continuing rigid caricature censorship in Russia, which lasted throughout the czarist regime, was satirized by the German journal Ulk's issue of January 26, 1906, which published a drawing depicting Czar Nicholas II's children presenting him with a blacked-out copy of the journal. When the children ask him, "What could this be?" he responds, "Me." Ulk informed its readers that to save the czarist authorities time and trouble, it had already taken the precaution of inking out the czar's face (Figure 2). (12)

Although prior censorship of caricatures was maintained until 1881 in France and throughout the nineteenth century in Russia, a

gradual loosening of censorship controls elsewhere after 1848 and the general breakdown of the so-called "concert of Europe" that had fostered general cooperation between the major powers led to

increasing numbers of post-publication incidents in which governments sought to suppress foreign caricatures or took actions against caricatures printed in their own countries which they felt

threatened their foreign policy objectives. For example, the caricature journal Il Fischietto, published in Piedmont, the only Italian state which survived the 1848 revolutions with a

relatively liberal regime, including an intact constitution and freedom of caricature, was forbidden in all of the other Italian states during the 1850s. They remained under the domination of

Austria or the reactionary rule of the Neapolitan Bourbons and the Pope. Even after most caricature restric¬tions were dropped when Italy became unified and independent after 1870, the Pope's

remaining autonomous stronghold of Vatican City banned sales of the bitterly anti-clerical Roman caricature journal L'Asino ("the Donkey"). (13)

In Germany, caricatures published outside of Prussia after 1848 which criticized Prussian policy often elicited Prussian diplomatic protests; such protests may have been influential, for example,

in leading the Bavarian government to crush the liberal-democratic caricature journal Leuchtkugeln in 1851. In 1882, the now-united German empire banned the French journal Chat Noir in

retaliation for its mocking caricatures of Bismarck (an action which the Chat Noir boasted of as a badge of honor), and similar action was taken by the German government against the

French journal Sourire for its issue of April 9, 1914, attacking German administration of Alsace. In 1898, Germany banned a special issue of the French journal Le Rire and

lodged a formal diplomatic protest against its publication due to its mocking drawings by artist Jean Veber, which ridiculed Kaiser Wilhelm's trip to Palestine. Especially objectionable was a

caricature which showed the German emperor and the Turkish sultan using Armenians for target practice, shortly after the Turkish government were widely accused of mass killings of Armenians

(Figure 3). The German government was especially sensitive to criticism of the Emperor's frequent foreign policy blunders; for publishing a caricature criticizing the same trip to Palestine,

Theodore Thomas Heine of the Munich-based democratic caricature journal Simplicissimus was jailed for six months. The Austrian government also found Simplicissimus so

threatening that it was banned for several months after its initial publication in 1896, leading Simplicissimus to publish a mocking caricature which depicted Austrian soldiers slashing

a poster advertising the journal with their sabers, while the Simplicissimus mascot, a bulldog, demonstrated his view of these proceedings by urinating on one of the officer's legs

(cover illustration). (14)

FIGURE 3. Germany officially protested this November 11, 1898 caricature in the French journal Le Rire which portrayed the German emperor shooting Armenians for sport.

The French government remained highly sensitive to artistic criticism from abroad and to the publication of caricatures in France that might threaten its foreign policy objectives during the post-1848 period. Under Napoleon III, for example, only caricatures which reinforced the government's foreign policy were allowed (for example, only on the eve of the Crimean War were anti-Russian cartoons permitted). French caricature journals during the 1870s were told they could not publish critical drawings of such foreign leaders as the Russian czar and the German emperor, and the journal Le Grelot was forbidden to publish a caricature criticizing the Swiss government without the approval of the Swiss ambassador (which he refused to give). Le Grelot complained on December 22, 1878, that this new restriction meant that "we are free to say whatever we want-subject to the inspection of half a dozen French censors and 50 or 75 foreign ambassadors." Apparently due to French diplomatic pressure, the Swiss government seized a caricature journal critical of French President MacMahon in 1873, and in 1877 Punch was once more banned from entering France, primarily as the result of publishing caricatures hostile to MacMahon, including one depicting him "stuck in the mud" of reactionary politics despite growing democratic sentiment in France. Punch reported on November 17, 1877, that MacMahon's government appeared to be "bent on keeping the voice of English opinion out of France" and "all that Punch can say is, that while France is as France is now, he would rather any day be stopped there than stop there." (15)

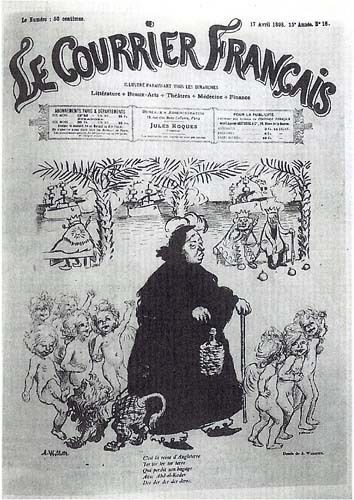

FIGURE 4. Britain officially protested this April 17, 1898 depiction in the French journal Le Courrier

Français of Queen Victoria carrying a bottle of rum.

Even the supposedly liberal English government protested against a number of caricatures published in France during the 1898-1903 gestation of the Anglo-French

entente. The British formally protested publication of a caricature by Adolphe Willette in Le Courrier Français of April 17, 1898, which showed Queen Victoria walking with a bottle of

rum in her hand (Figure 4). The British again protested in the aftermath of a special issue of Le Rire of November 23, 1899, designed by Willette, which bitterly attacked British

imperialism ; for example, one drawing depicted a crucified Ireland asking, "Oh God, who I have long implored! Are you English?" (Figure 5) (16)

FIGURE 5. Britain protested this November 23, 1899 issue of the French journal Le Rire, portraying a

crucified Ireland.

One of the most famous diplomatic incidents in the history of caricature was provoked by an anti-British issue of L'Assiette au Beurre published on

September 28, 1901, designed by jean Veber. Filled with bitter attacks on the use of concentration camps by the British during the Boer War, the most sensational caricature depicted "impudent

Albion" in the form of a woman displaying her backside to the world, upon which could be seen the features of King Edward VII. King Edward personally complained about this drawing to French

ambassador Paul Cambon, who wrote to his brother that the design was "scandalous," but conceded that it was "very well done" and displayed an "exact resemblance" of the king. Either in response

to British protests or out of its own desire to preserve the Franco-British entente, the French government refused to allow sales of the caricature on the public streets unless it was modified.

Although prior censorship of caricature had been abolished at last in France in 1881, the government still asserted the right to administratively (i.e., without judicial action or appeal) ban

street sales of caricature journals. L'Assiette au Beurre responded by repeatedly reprinting the issue with Albion's backside gradually and increasingly concealed; at first, by a

semi-transparent purple slip which still allowed King Edward's features to peek through, but eventually-in apparent response to continuing government harassment-by a completely opaque dark blue

skirt (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. French officials barred streets sales of the September 28, 1901 issue of L'Assiette au Beurre, which as originally published (upper left), portrayed "Impudent Albion (England)" showing its true face to the world during the Boer War via a depiction of King Edward VII on the bared bottom of a laughing female soldier. The magazine responded by repeatedly reprinting the sold-out issue and gradually covering up the king's features.

No doubt due to the enormous publicity aroused by the controversial caricature, the September 28 issue was eventually reprinted 10

times, sold an unprecedented 250,000 copies, and was acclaimed by L'Assiette au Beurre as a "success without precedent." Two subsequent anti-British issues of L'Assiette au

Beurre were also banned from public sales by the French government, including the June 28, 1902, issue, which depicted the legacy of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes as a pile of skulls

(Figure 7) and a January 3, 1903, issue which portrayed a Frenchman pointing out a beating to a British tourist while declaring, "That's exactly what you have done to the Boers [in South Africa]

and what you are now doing to the Venezuelans." The well-known sensitivity of the British to pictorial criticism of their Boer War policy apparently also led German authorities in 1901 to

confiscate an issue of Simplicissimus which portrayed a towering, obese Edward VII trampling tiny concentration camp inhabitants and complaining, "This blood is splashing me from head to

toe. My crown is getting filthy." (17)

FIGURE 7. Apparently for fear of complicating diplomatic relations with England, French officials barred street sales of this June 28, 1902 issue of L'Assiette au Beurre, depicting the legacy of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes.

L'Assiette au Beurre also had difficulties with the French government for publishing cartoons critical of countries other

than Britain. Two issues bitterly critical of Russian Czar Nicholas II's bloody repression of the revolution of 1905 were banned from sales on the street. Apparently this was done not because of

a request by the Russian ambassador but because the French government viewed the caricatures as threatening the Franco-Russian alliance. The cover of its February 5, 1905, issue depicted a

magnificently clothed but blood-spattered Tsar Nicholas II in the aftermath of the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 1905, and the November 11, 1905, cover depicted the tsar's head on a pike,

suggesting that the only solution to Russian autocracy was his death. Also banned from street sales was L'Assiette au Beurre's November 25, 1905, issue, which mocked the fat and

autocratic King Carlos I of Portugal during his 1905 visit to Paris by portraying him as a pig-like figure.

L'Assiette au Beurre reacted with intense anger to these arbitrary decisions to ban sales. It complained for example, on November 25, 1905, that the police, "having both the power of

censor and absolute monarch, stifle and suppress according to their will, all ideas which don't please them." On December 9, 1905, L'Assiette au Beurre added : “The Empire [of

Napoleon III], we have been repeatedly told, was the regime of arbitrariness; the republic is the regime of liberty. But it is easy to verify that the procedures of the republican government are

identical to those of the imperial regime.” (18)

During World War I, the perceived power of political caricatures was again repeatedly demonstrated by the actions of European governments. To help enlist American entry into the war, the British

sent cartoonist Louis Raemaekers to the United States. His caricatures were later assessed by Times war correspondent Sir Perry Robinson as making him among the six men, including statesmen and

army commanders, whose influence and efforts had been among the most decisive in the war. Meanwhile, Germanplanes dropped copies of the "impudent Albion" issue of L'Assiette au Beurre

over British trenches in France, while the British responded by dropping over Germany copies of the 1898 Le Rire issue mocking the Emperor's trip to Palestine. German Kaiser Wilhelm II's

hatred for critical caricatures became so well known that the London Opinion of June 26, 1915, published a cartoon showing Wilhelm signing a document while sitting before a display of drawings,

entitled, "The Kaiser signing the death warrant of certain English caricaturists." (19)

Authorities in nineteenth-century European regimes viewed caricature as a powerful weapon. In numerous incidents they sought to suppress foreign caricatures which criticized them or to ban

domestically-produced caricatures which they feared would threaten their diplomatic relations. They also occasionally used caricatures as instruments of government foreign policy, as during World

War L From the historian's perspective, incidents in which caricatures were banned not only help to demonstrate their power but also give us enormous insight into the fears and thoughts of ruling

élites. As French legislator Robert Mitchell told his colleagues in 1880, while drawings which gained "official favor" could be freely displayed and sold, those which "displease the government

are always forbidden" and thus censorship decisions provided : “... a valuable indicator for the attentive observer, curious for precise informa¬tion on tastes, preferences, sentiments, hates

and intentions of those who have the control and care of our destinies. In studying refused drawings and authorized drawings, we know exactly what the government fear and what it encourages, we

have a clear revelation of its intimate thoughts.” (20)

Robert Justin Goldstein, Oakland University

Autres articles sur la caricature

Notes

(1) An

excellent general survey of nineteenth-century Europe caricature is Ronald Searle, Claude Roy, and Bernd Bornemann, La Caricature: Art et Manifeste (Geneva: Skira, 1974). There is also much

useful material in: Edward Lucie-Smith, The Art of Caricature (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981); William Feaver, Masters of Caricature (New York: Knopf, 1981); James Patron, Caricature

and Other Comic Art in All Times and Many Lands (New York: Harper, 1878); Bevis Hillier, Cartoons and Caricatures (New York: Dutton, 1970); and Arsène Alexandre, L'Art du Rire et de la Caricature

(Paris: Quantin, c. 1900). On France, see John Grand-Carteret, Les Moeurs et la Caricature en France (hereafter cited as France) (Paris: Librairie Illustrée, 1888) and Robert Justin Goldstein,

Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989). On Germanic Europe, see John GrandCarteret, Les Moeurs et la Caricature en

Allemagne, en Austriche et en Suisse (hereafter cited as Allemagne) (Paris: Hinrichsen, 1885) and Ann Allen, Satire and Society in Wilhelmine Germany: Kladderdatsch and Simplicissimus, 1890-1914

(Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1984). On Russia, see David King and Cathy Porter, Images of Revolution: Graphic Art from 1905 Russia (New York: Pantheon, 1983). On Italy, see Rosanna

Maggio-Serra, "La Naissance de la Caricature de Presse en Italie et le Journal Turinois `Il fischietto'," Histoire et Critique des Arts, 13/14 (1980), 135-58.

(2) James Cuno, Charles Philipon, and La Maison Aubert, "The Business, Politics and Public of Caricature in Paris, 1820-1840." (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1985), 51; Archives Nationales,

Paris (hereafter AN), F18 2342.

(3) AN, F18 2342.

(4) Claude Bellanger et al., Histoire Générale de la Presse Française, vol. 2 (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1969), 352; Mary Lee Townsend, "Language of the Forbidden: Popular Humor in

'Vormarz' Berlin." (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1984), 277, 281; Moshe Carmily-Weinberger, Fear of Art: Censorship and Freedom of Expression in Art (New York: Bowker, 1986), 157.

(5) Archives Parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, vol. 98 (Paris: Paul Dupont, 1898), 407, 741, 744; Journal Officiel (hereafter JO), 8 June 1880, 6212-13.

(6) David Kunzel, The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet front c. 1450 to 1825 (Berkeley: University of California, 1973), 443.

(7) Hillier, 45; Robert B. Holtman, Napoleonic Propaganda (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950), 166.

(8) André Blum, "L'Estampe Satirique et la Caricature en France au XVIIIe Siècle," Gazette des Beaux-Arts 52 (1910): 379-92, 53; (1910): 69-87; Searle, 95.

(9) André Blum, "La Caricature Politique en France sous le Restauration," La Nouvelle Revue 35 (1918), 119.

(10) Bellanger, 45-56; Searle, 157, 161.

(11) Punch, 4 (1843), 75, 155.

(12) Townsend, 238.

(13) Maggio-Serra, 145; John Grand-Carteret, Crispi, Bismarck et la Triple-Alliance en Caricatures (Paris, 1891), 11-13.

(14) Grand-Carteret, Allemagne, 122; Lucie-Smith, 81; Jacques Lethève, La Caricature et La Presse sous La IIIe République (Paris: Armand Colin, 1961), 114, 116; Florent Fels, "La Caricature

Française de 1789 à Nos Jours," Le Crapouillot 44 (1959), 68; Fritz Arnold, One Hundred Caricatures from Simplicissimus, 1896-1914 (Munich: Goethe Institute, 1983), 14.

(15) Grand-Carteret, France, 399-400; Le Don Quichotte, May 19, 1877; Le Grelot, December 22, 1878.

(16) Searle, 228, 231; Philippe Roberts-Jones, La Caricature du Second Empire à la Belle Epoque (Paris: Le Club Français du Libre, 1963), 404; Lethève, 118.

(17) Elisabeth et Michel Dixmier, L'Assiette au Beurre (Paris: Maspero, 1974), 220-23; Raymond Bachollet, "Satire, Censure et Propagande, ou le destin de l'Impudique Albion," Le Collectionneur

Française, 174 (December, 1980), 14-15; 176 (February, 1981), 15-16; Allen, 228.

(18) Dixmier, 222-23.

(19) Stanley Applebaum, French Satirical Drawings from "L'Assiette au Beurre," (New York: Dover, 1978), xiv; Hillier, 118.

(20) JO, 8 June 1880, 6214.

/image%2F0947248%2F20141221%2Fob_0040c8_cc-14383b.jpg)